Director: F.W. Murnau

Country of origin: Germany

Language: Silent

B&W

Ok, admittedly, this might feel like being thrown in at the deep end but bear with me, for this film is a wonder to behold.

The first (and arguably still the best) screen incarnation of Dracula, is Max Schreck's terrifying portrayal of the blood-sucking, sexual predator Count Orlok. But what he lacks in looks he makes up for in style, wit and panache. No, not really, he's just such a horrific creation, he will set your bowels to churning and skin to crawling.

Nosferatu is important for several reasons.

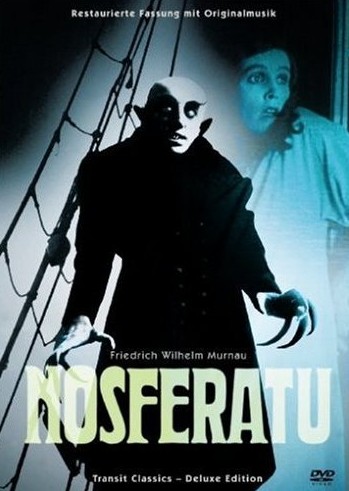

|

| Classic low angle shot |

It is a major early work by F.W. Murnau, a former theater director, who along with the Russian director, Sergei Eisenstein, American D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin, would really create the blueprint for what we now speak of as film language.

While Griffith was a pioneer of epic staging; Einstein more or less invented editing and Chaplin became a master of the set piece to rival them all; Murnau brought the theater concept of mise-en-scene to the party. I'm not saying he invented it, but few were doing it as well as him, as early as him.

All those low angle shots giving an impression of power, or high angles that make characters look vulnerable; Murnau was at it in 1922.

blocked movement; Murnau was an obsessive perfectionist, sometimes driving his collaborators close to insanity, if the stories are to be believed.

This "faction" is captured wonderfully in the curious, and apparently little seen film, Shadow of the Vampire (2000). A fictionalised account of the making of Nosferatu, it suggests that the venerated German stage actor Max Schreck, who plays the Count, was in fact a real vampire, whom crazed Murnau tempts to play the role with the promise that he will get to feast on the blood of his co-stars. John Malkovich is perfectly cast as Murnau, and Willem Dafoe delivers a predicably batty turn as the immortal Schreck. An interesting counterpoint to his other wonderful turn as an immortal: Jesus Christ in Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

This "faction" is captured wonderfully in the curious, and apparently little seen film, Shadow of the Vampire (2000). A fictionalised account of the making of Nosferatu, it suggests that the venerated German stage actor Max Schreck, who plays the Count, was in fact a real vampire, whom crazed Murnau tempts to play the role with the promise that he will get to feast on the blood of his co-stars. John Malkovich is perfectly cast as Murnau, and Willem Dafoe delivers a predicably batty turn as the immortal Schreck. An interesting counterpoint to his other wonderful turn as an immortal: Jesus Christ in Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)Nosferatu is a key work of German Expressionism, an art movement whose cinematic offshoot was visually defined by jagged angles and geometrically absurd, wildly unrealistic sets (see also: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari). The result was a nightmarish visual landscape which reflected both the metal turmoil of the characters and the psychologically disturbing themes being explored.

|

| Jagged, angular shadows |

These frenzied tales of madness could be interpreted as attempting to confront the dread that festered in the aftermath of WWI. The impact on the European psyche of the cataclysmic devastation of that war cannot be over-estimated.

A very real fear was emerging that this rapidly changing and modernizing world, where death could be delivered to men by the tens of thousand, may be spiraling out of control. The new world was viewed ambiguously at best, for it seemed to hold within itself the seeds of its own destruction, on a mass scale. Nosferatu reeks with the madness of this death dealing.

Artists like Murnau would, notice early the changes occurring in Germany as the Nazis began to emerge in the 1920s; they would eventually brand his kind of cinema too intellectual. But Murnau escaped early, avoiding the oppression to come, like many German artists (not necessarily all Jewish, artists by their nature have tended to be liberals) to the welcoming arms of Hollywood where he would make the magnificent Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927).

He died in a car accident in 1931.

Links:

To watch Nosferatu CLICK HERE

To watch a trailer for Werner Herzog's chilling remake: Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) CLICK HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment